|

Manuel Portela

Grupo de Estudos Anglo-Americanos

Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Coimbra

3004-583 Coimbra

Portugal

Tel. +351 239 859982

Fax: +351 239 836733

mportela@fl.uc.pt

Keywords

digital poetry, concrete poetry, intermedia genres, computer animated

poetry, Augusto de Campos, E.M. de Melo e Castro, Tiago Gomez Rodrigues

Abstract

I argue that there is an intrinsic connection between concrete poetics

as a theory of the medium (i.e., of language, of written language, and

of poetical forms) and digital poetics as a theory of poetry for the

digital medium. This link is clearly seen in the use of concrete poems

as storyboards and scripts for electronic texts, both in composing text

for graphic interface static display and for animation. This essay

deals with the adoption of electronic media by concrete poets, with

examples from the work of Brazilian poet Augusto de Campos (1931-), and

Portuguese poets E.M. de Melo e Castro (1932-) and Tiago Gomez

Rodrigues (1972-).

Introduction

I argue that there is an intrinsic connection between concrete poetics

as a theory of the medium (i.e., of language, of written language, and

of poetical forms) and digital poetics as a theory of poetry for the

digital medium. This link is clearly seen in the use of concrete poems

as storyboards and scripts for electronic texts, both in composing text

for graphic interface static display and for animation. It is as if the

concrete approach to language and form, because of its constructivist

and objectivist emphasis, anticipated the kind of reflection on media

set in motion by the electronic page. Close attention to the visibility

of language and to the materiality of reading, two of the central

tenets of concretist texts, also underlie many of the poetic attempts

to use the specific properties of electronic textuality in digital

forms. This essay deals with the adoption of electronic media by

concrete poets.

I want to point to the confluence of concrete and digital poetics in

the work of Brazilian poet Augusto de Campos (1931-), and Portuguese

poets E.M. de Melo e Castro (1932-), and Tiago Gomez Rodrigues (1972-).

The particular significance of Augusto de Campos and E.M. de Melo e

Castro for my argument is that they were both pioneers of concrete

poetics in the 1950s and 1960s and they have adopted computers in their

creative process in the early stages of the development of personal

computing in the 1980s. Tiago Gomez Rodrigues, on the other hand, is a

digital and multimedia artist, who, in his digital film-poem Concretus

(2002), self-consciously extends concretist research of the materiality

of sound and writing into the textuality of the digital medium, in

which sound, text, movement and music combine in new intermedia genres.

The Poem As A Language Generator

|

|

| |

The

adoption of computers as a means for literary creation has been

fostered by concrete poetics. Because of its internalization of a

theory of language as a structural system of signs, the concrete poem

laboratory explores the projection of the paradigmatic axis into the

syntagmatic axis. This probabilistic game with phonetic and semantic

similarities and differences is spatialized on the page, in such a way

that it foregrounds the fact that a text is always a set of

instructions for reading itself. Consequently, the combinatorial

procedures that have generated the rhetorical and typographic code of

the poem become visible on the textual surface. In retrospect, the poem

appears as a script of meaning, even if this meaning is not entirely

determinable. Despite their reliance on the ambiguity that results from

superposition of sense and sound states, many concrete poems focus on

language and print as technical devices for producing and exchanging

information. See, for example, Edwin Morgan’s Message Clear (1965),

where the bits and bytes that produce verbal meaning have been

decomposed, as if the poem intended to present us with the machine-code

for the miracle of transubstantiation that occurs in linguistic signs

(Figure 1). This is the kind of metalinguistic analysis that

signals concrete self-reference to the poem’s information code. For

concrete aesthetics, the dynamics of a syntactical combination that

resulted from phonetic and graphical attractions and lexical

cross-breeding is the guiding principle of composition.

|

|

| |

Its

conscious and subconscious workings may be observed both below and

above the word level: in the first case in the agglutinations,

prefixes, infixes, suffixes, and various types of fragmentation of both

lexemes, morphemes and even graphemes; in the second case, at the

higher level of syntactic units, sentences, and texts. These procedures

subject the semantic and ideological level of language to a

combinatorial art that, at one and the same time, destroys and

reconstructs the texture of inferences and recurrences that upholds

discursive coherence. Concrete poetics moulds the structural and

psychic materiality of the sign by linking its formal linguistic

properties with the mind processing of those properties. Thus it is a

poetics of spoken and written language, as much as it is a poetics of

hearing and reading. Its hermeneutics starts at the physiological

processing of audiovisual input, which transmutes the poem into a

cyborg, that is, a cybernetic simulation of meaning as a specific

processing of information.

From

this point of view, the concrete poem is a kind of language generator

which provides a microcosm both of the linguistic processes of word and

sentence creation, and of the more basic and fundamental structuring

processes of the phonetic, syntactical, semantic, and pragmatic

elements that produce language. Language is not a mere repertoire of

given elements, classes of elements, and combinations of those classes,

but it is above all the possibility of expanding elements, classes, and

combinations. Such a virtualization of the infinity of language has

implied that poetical production should also take place at the more

fundamental levels of the linguistic sign and written signification.

Language as a means of production had to be pulled apart and

scrutinized in its microscopic materiality.

Peeling

of words and phonic fracture, for example, were proclaimed as

programmatic principles by Haroldo de Campos (1929-2003) in his early

series of five poems ô â mago do ô mega (1955-56). As happened in konstellationen constellations constellaciones

(1953) by Eugen Gomringer, this semiotic phenomenology of language

explodes the semantic units that were crystallized in lexemes and

morphemes by means of fragmentation and unexpected recombination. Yet,

by revealing the mathematics of language that turned the poems into

structures of meta-data, the concrete poem often remains entrapped in

the self-reflexivity of its verbal and iconic tools.

It

is not a matter of coincidence that the poem about the poem (always a

serious candidate to being the most frequent topic in the history of

any type of poetry) has become perhaps the archi-theme of concrete

poetry, as if every single poem had to be a ars poetica at

the same time. That is clearly the case with Haroldo de Campos and

Augusto de Campos, who, over the years, have been parodying and

quoting, again and again, their own constellations of authors and texts

in order to write about the poetical act (Homer, Chuang-tsé, Li Po,

Guido Cavalcanti, Dante, Camões, Goethe, Novalis, Poe, Mallarmé,

Maiakóvski, Khlebnikov, Pessoa, Pound, Joyce, T.S. Eliot, Sousândrade,

Oswald de Andrade, Mário de Andrade, João Cabral de Melo Neto, O

Cântico dos Cânticos, Eclesiastes, John Cage, etc.). This never-ending

attempt at making the poem a mirror of itself is one of the

poetechnical consequences that follow from the concrete emphasis on the

objective, autonomous, and self-enclosed nature of the poem.

Topographic Poetics: Concrete Space Becomes Digital Space

For

Augusto de Campos, concrete aesthetics was trying to extend and

redefine the typographical objectivity of earlier modernist conceptions

in a new technological context: That the program or script for the

meaning of a text can be or has to be formalized is perhaps the price

to be paid for the theoretical dimension of a language poetry that

defines itself in those terms, and that puts most of its emphasis in

inter-semiotic processes. In their attempt to unify the activities of

criticism, poetry, and translation, by means of the “the critical

devouring of the universal legacy” (Haroldo de Campos), concretists

have developed a poetical consciousness of language that matched the

science of linguistics and the science of cybernetics of our own time.

More important than reifying the poem as a finished object, concrete

poetry has contributed to the writing and reading of the poem as

process for producing meaning. That ambitious program for researching

self, language, and literary forms continues in the textual fields of

the information age. The seamless way in which Melo e Castro and

Augusto de Campos have transposed many of their works of the 1960s and

1970s into the digital medium suggests that there may be continuity

between concrete space and digital space.

|

|

| |

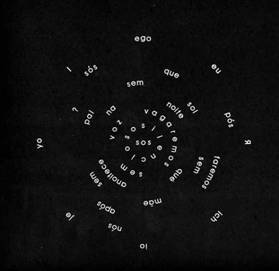

Two examples will illustrate this transition between static paper page and kinetic computer display. SOS,

by Augusto de Campos, was originally written in 1983 (published in book

form in Despoesia, 1994, p. 27 - Figure 2, above). The title-word sos

(which, in Portuguese, means S.O.S. and is also the plural form of

“alone”) stands at the center of seven circles of letters and words. At

once a cosmological and psychological constellation, the ideogram can

be read clockwise and counterclockwise, from the outer to the inner

circle and vice-versa, and in various combinations of those four

movements. The outermost circle is made of eight words, in eight

different languages, for the personal pronoun “I”. The text seems to

re-enact the process of awareness from individual consciousness to

human consciousness, by reference to cosmological mystery of origin,

and also to human mortality. This diagrammatic reflection upon human

solitude in the universe mimics planet orbits (by allusion to past and

present scientific and literary representations) and also the pattern

of electromagnetic waves spreading outwards from a source. The

opposition “night”/ “sun” and “voice”/ “silence” are visually

translated to the black and white surface of the page.

The second poem is a computer animation of SOS developed by Augusto de Campos using Macromedia Flash [See above: Augusto de Campos, SOS (2003)]. It was first published in the CD-ROM clip-poemas (1997-2003), which comes with his latest book Não Poemas (2003).

The digital version adds color, movement, and sound to the original

text, using it as script or notation for its digital re-mediation. Some

of the possible reading paths have now been animated: the sequence of

frames offers the viewer a privileged reading sequence. The

simultaneity of the spatially organized page has been broken down by

cinematic temporality, which is now a simulacrum of the reading

movement, directing the viewer’s attention to certain syntactical

operations.

As the text

unfolds, reading itself as it were, the reader becomes aware of the

powerful association mechanisms that its ideogrammatic structure

contained, including the way in which the act of reading the poem was

designed so that it could be experienced as a replica of the

cosmological questioning of the universe. While the animation silently

reads the text, voices materialize the ultimate human horizon of

self-consciousness, interrogation, silence, death, and oblivion. Echoes

and superposition of voices further stress this individual-collective

cosmological ontology of hope and despair.

The

digital medium, especially after the combined development of hypertext

and large-scale computer networks, has led to the creation of literary

genres that are specifically digital, i.e., genres that adopt the

properties of the software and of the means of computational display as

structural elements of poetic and narrative forms. Moreover, the

digital medium has enabled authors to formalize the intra-textual and

inter-textual connections, and it has also permitted the development of

certain textual virtualities that are inherent to various typographical

genres. That is what happens when typographic visual poetry is

converted into kinetic poetry, or when combinatorial paper fiction

becomes hyperfiction. In these cases, electronic transposition and

publication is not a mere substitute for paper, because it interferes

with specific textual aspects, and thus reconfigures the formal and

semantic properties of objects according to the axis of electronic

semiosis.

The Movement Of Reading

The

Portuguese poet E.M. de Melo e Castro is also the author of an early

series of computer-animated poems, Signagens (1985-1989) [1]. Those

sequences adapt 18 of his concrete and visual texts. Again, by

re-reading the paper versions of the poems, animation may be said to

re-write those texts with reference to the specific reproduction

technology that they are now using. In some cases, what the viewer sees

is the actual accomplishment of what were suggestions of movement in

the original paper version. However, a careful analysis of the

suggestions of movement will discover that these have to be decomposed

in two different types of reverberations: while one type is a function

of imagining an iconic mimetic between ideogram and external reference,

the other type is a function of the physical and semiotic act of

reading the ideogram. We should bear in mind that many visual poems

contain this double rationale of movement, i.e., a movement that is

symbolically and mimetically associated to the object, and a movement

that is the effect of the act of reading. What this means is that

poem-object and reader-subject are split and re-joined in the field of

perspective created by the consciousness of reading as a movement in

the outer space of the page and in the inner space of the mind.

Animated

versions make clear this multi-layered polysemy of movement that takes

place in the mind of the reader of a visual poem. What often baffles

readers of concrete texts is the paradox of finding themselves before

minimal signs that are at the same time highly charged of references

and meanings. For those readers, what appears as an impenetrable

surface-only sign and an unimaginable single-word palimpsest work to

reinforce the prejudice against concrete poetics. The fact that

many poems attempt to break the discursive chains associated with the

elements contained in the poems, very often discarding syntactic

connectors, turns texts into a challenging notation that readers have

to learn to read. The word, written or spoken, is never entirely taken

for granted and even self-similarity, when it exists, is not

necessarily a trivial poetical device, at least in the most interesting

and complex texts.

In fact,

animated versions, when they are but sets of instructions for reading

ideogrammatic or pictogrammatic poems, can become didactic and,

sometimes, they provide a poorer viewing/reading experience than the

paper original. It should be noted however that many of the digital

versions of concrete texts have added extra layers of meaning by

integrating specific properties of digital production and reproduction

technologies, such as the use of color and color effects,

three-dimensionality, framing and point of view, human voice, sound

effects, music, etc. The syntax of movement and sound, as well as the

editing of image frames, enable texts to acquire the material and

formal properties associated with cinema, for instance. Melo e

Castro’s computer text animations are outstanding in this respect: so

much so that you can claim that those texts seem to have been waiting

for electronic media [2].

|

|

| |

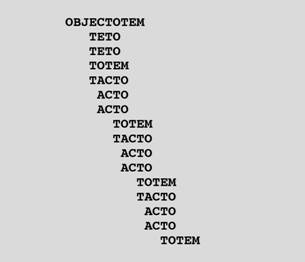

One

example is the version of his 1962 poem objectotem (Figure 3, ab).

While the frames of the computer version re-create the reading

sequence, highlighting the internal echoes between new words and the

words contained in agglutinated word-object that makes the title, they

also add a vocal interpretation (chorus and drums) that reinforce the

representation of the poem-object as a collective totemic icon

celebrated through ritual acts. Objectivist aesthetic theory is related

to the archaic magical use of language whereby the computer version

becomes a sort of ethnographical record of concrete forms. Vocalization

and iconicity are used to suggest primeval body rhythms and primeval

forms of writing [3].

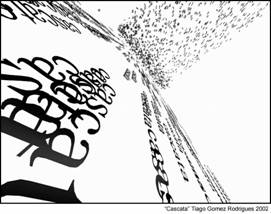

Tiago Gomez Rodrigues’ film Concretus

(2002) is a six-minute narrative that contains digital animations of

five ideograms: “tontura” by E.M. de Melo e Castro; “arranhisso”, by

Salette Tavares (1922-1994); “cascata”, “cubo” and “esfera”, by Tiago

Gomez Rodrigues (Figures 4 and 5, below). Tiago Rodrigues is also the

author of the completely digital soundtrack. This film is an inspiring

example of the marriage between concrete aesthetics and digital

technology. In Concretus, the reflection upon the specific

properties of the medium takes place in the ingenious fore-grounding of

three-dimensional digital animation techniques (shot angles, surface

textures, light sources, shadows, etc.). Concretus is not simply

illustrating the objectivist principles of concrete poems in a 3-D

environment. Elaborate suggestion of camera movement around and inside

the word-objects turns optical consciousness of the cinematic illusion

into a central element of this narrative about the nature and

possibility of concreteness in representation.

|

|

| |

The

tension between iconicity/mimesis/self-similarity, on the one hand, and

the abstraction provided by written signs and synthetic sounds, on the

other, is the driving force of this work. This tension shows how a

specific digital intermedia form has adopted concrete poetics to

explore its own material possibilities for meaning. The distance

between signifier and signified cannot be overcome, even when the

signifier is the signified, because that is the interval that makes

meaning possible. Considered as a narrative, this digital film-poem

points to the paradoxical nature of its objects as concrete

abstractions that exceed the pictographic logic that seems to contain

them. The movement suggested by the sequence of frames, shots, and

angles is a radical re-writing of the original ideograms, asking for a

whole new level of engagement with the concreteness of text.

|

|

| |

As

for those genres that are intrinsically digital, mention should be made

of the integration of the reproduction technologies for sound, and for

reproduction and animation of images (digital or photographic) with the

technologies for the reproduction of text. The appearance of iconic and

cinematic genres, capable of bringing together elements of cinema,

video, and music with narrative and poetical forms of textual nature,

will probably be one of the future developments, as I can see in Tiago

Gomez Rodrigues work. I can imagine, for instance, a new genre in which

text and image will come together in a way that is different from what

happens in comics books and in graphic novels, displaying an ensemble

of properties that we now associate either with video, cinema, music,

computer games, virtual reality, poetry, or the novel.

Theorists

and practitioners of digital literary art, such as Michael Joyce, Loss

Pequeño Glazier, Matthew Kirschenbaum, and Johanna Drucker, have argued

that the technological features of the digital medium imply a new

consciousness of textuality. For the on-going examination of the

specificity of the digital medium, many of the most innovative

experiments of 20th-century literature appear to be extremely relevant,

because of their awareness of the fundamentals of language and textual

display. According to Glazier, the electronic on-line space, for

instance, cannot be seen simply as an environment or support for

writing, since it is already an instance of writing by itself. From

this follows the realization that poetical textures are already

embedded in the poeisis that defines the Web. In what he refers to as

the digital field, Glazier identifies three forms of electronic

textuality: a) hypertext; b) visual or kinetic text; c) works in

programmable media (see GLAZIER,

http://epc.buffalo.edu/authors/glazier/dp/intro1.html)

In my view, three properties justify the connection between the

concrete poem and the digital poem that I have tried to outline: 1st)

the spatialization that occurs in the concrete text is similar to the

topographic and iconic writing of digital interfaces; 2nd) the creation

of non-sequential reading paths (with multiple trajectories resulting

from the breaking-up of language units) is similar to the

non-sequential writing of hypertext; 3rd) the explosion of the text

into a network of allusions anticipates the notion of “literature

as a system under construction of interlinking documents” (Ted Nelson).

By means of multiple cultural associations and literary allusions,

densely packed in minimal elements, the concrete poem appears as

cluster of constellated references and meanings. Because of those three

properties, the opening of text to the probabilities of language by

means of combinatorial procedures, which was the defining principle of

concrete poetics, can now continue in the digital medium.

I finish with another poem by Augusto de Campos, both in static and kinetic versions: sem saída

[no exit] (Figure 6, right). The author is playfully subverting

the charge, aimed at the concretists, that they had led poetry to a

dead-end street. As is characteristic with Augusto de Campos, the

attempt to find a way out is literally materialized in the semiotic

processing of signs that is required from the reader. He/she has to

make sense of the lines in different colors that cross and superimpose

on the page

With its echo of Theseus in the labyrinth, in sem saída,

as in many other poems by Augusto de Campos, the act of reading with

the eye and with the mind is always the quintessential hermeneutic

experience. Once the reader has deciphered all the lines, he/she will

realize that it is not yet the way out: that was only Augusto de

Campos’ way out, his own individual thread for traveling the labyrinth

of life, language, and self. Crossword puzzle on the printed page, or

computer mouse-clicking on the electron screen or liquid crystal

display, it’s up to the reader to find his/her way. Moreover, sem saída is also a self-reflective ars poetica about

the electronic reading space, in which eyes and hand attempt to find

their way in the multiple trajectories signaled by the graphical

interface of hypertext pages. In its joyful and ironic celebration of

the achievements and shortcomings of concrete poetics, the rainbow

colors of sem saída seem to point to yet another tentative

and provisional way out, this time offered by the digital medium as a

way for extending and exploring the poetic insight about the strange

mediations that bring the world to the self in the labyrinth of

language [See above: Augusto de Campos, sem saída (2003)].

Notes

1. Signagens includes the following videopoems: As Fontes do Texto,

Sete Setas, Sede Fuga, Rede Teia Labirinto, Vibrações, Um Furo no

Universo; Come Fome; Hipnotismo; Ponto Sinal, Polígono Pessoal, O

Soneto, Oh Poética dos Meios, Concretas Abstracções, Objectotem,

Escrita da Memória, Infografitos, Ideovídeo, Diazulando, Metade de Nada

and Vibrações Digitais de um Protocubo, Do Outro Lado. Other video and

computer poems by Melo e Castro: Roda Lume (1968, 2 min. 43 s., remade

in 1986), Vogais as Cores Radiantes (1986, 3 min. 10 s.) and Sonhos de

Geometria (1993, 30 min., original soundtrack by TELECTU).

2.

In fact, Melo e Castro produced his first film-poem in 1968, Roda-Lume

[Wheel-Fire]. A computer animation of this text was later included in

the series Signagens (1985-1989).

3.

For copyright reasons, Signagens has never been published in CD-ROM

format, and so it is not possible to include an example here.

Cited Works and Further Reading

Campos, Augusto De. Não Poemas, São Paulo (Editora Perspectiva, 2003),

includes CD-ROM with the series Clip-poemas (1997-2003).

Campos, Augusto De. Despoesia, São Paulo, (Editora Perspectiva, 1994).

Campos, Augusto De. http://www2.uol.com.br/augustodecampos/home.htm (last accessed 14 Aug 2004)

Drucker,

Johanna. “Intimations of Immateriality: Graphical Form, Textual Sense

and the Electronic Environment”, in Elizabeth Bergmann Loizeaux &

Neil Fraistat, eds., Reimagining Textuality: Essays on the Verbal,

Visual and Cultural Construction of Texts (Madison: University of

Wisconsin Press, 2002, pp. 152-177).

Goldsmith, Kenneth. From (Command) Line to (Iconic) Constellation, in http://www.ubu.com/papers/goldsmith_command.html (2002) (last accessed 14 Aug 2004)

Glazier,

Loss Pequeño. Digital Poetics: The Making of E-Poetries (Tuscaloosa:

University of Alabama Press, 2002). First chapter, “Language as

Transmission: Poetry’s Electronic Presence”, also available at http://epc.buffalo.edu/authors/glazier/dp/intro1.html (last accessed 14 Aug 2004)

Greene,

Roland. “From Dante to the Post-Concrete: An Interview With Augusto de

Campos”, The Harvard Library Bulletin, Summer 1992, Vol. 3, No. 2, in

http://www.ubu.com/papers/decampos.html (last accessed 14 Aug 2004)

Joyce,

Michael. Of Two Minds: Hypertext Pedagogy and Poetics (Ann Arbor: The

University of Michigan Press, 2002 [1st ed. 1995]).

Kirschenbaum,

Matthew G. “Editing the Interface: Textual Studies and First Generation

Electronic Objects”, in TEXT: An Interdisciplinary Annual of Textual

Studies, 2002, Vol 14 pp 15-52.

Melo E Castro, E.M. Signagens (Lisboa: Universidade Aberta, 1985-89) [VHS video, 1h 30min.].

Melo E Castro, E.M. Trans(a)parências (Sintra: Tertúlia, 1989).

Melo

E Castro, E.M. Infopoesia: produções brasileiras (1996-99), in

http://hosts.nmd.com.br/users/meloecastro/ (last accessed 14 Aug 2004).

Morgan, Edwin. The Second Life (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1980) [1st. ed. 1967].

Morgan, Edwin. http://www.edwinmorgan.com/ (last accessed 14 Aug 2004).

Nelson, Theodor Holm. Literary Machines, Mindful Press/ Eastgate Systems.

“Questionnaire of the Yale Symposium on Experimental, Visual and

Concrete Poetry since the 1960’s” (April 5-7, 1995), Questions

formulated by Eric Vos & Johanna Drucker. Replies by Augusto de

Campos, translated by K. David Jackson, in http://www2.uol.com.br/augustodecampos/yaleeng.htm (1982) (last accessed 14 Aug 2004).

Portela,

Manuel. “Hipertexto como Metalivro”, in Ciberliteratura, Coimbra:

Ariadne Editora, (2004), pp. 69-83 [forthcoming]. Also available at

http://www.ciberscopio.net/artigos/tema2/clit_05.html (last accessed 14

Aug 2004).

Rodrigues, Tiago Gomez. Concretus: um concretismo animado (Marquês Produções, CD-ROM, 2002).

Author Biography

Manuel Portela has written books of visual and sound poetry, as well as

a number of satirical poems. His early poems have been collected in

Cras! Bang! Boom! Clang (1991) and Pixel Pixel (1992). He organized an

international exhibition of visual and concrete poetry in 1993 -

Wor(l)d Poem/ Poema Mu(n)do, which was held at the Museum of Figueira

da Foz, Portugal. He has also exhibited his own visual poetry and he

has created several digital poems. Since 1994 he has published 10

volumes of translation, including the first Portuguese editions of

William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1994) and

Laurence Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy (2 vols,

1997-98). He was awarded the National Prize of Literary Translation for

Tristram Shandy. Many other translations have appeared in Portuguese

and Brazilian journals and anthologies, including poems by Samuel

Beckett, Edwin Morgan, Tony Harrison, John Havelda, Charles Bernstein,

Mike Basinski, Bill Howe, Ron Silliman, Bob Perelman, Dennis Cooley,

Robert Kroetsch, Roy Miki, Don Paterson. He has written short plays

both for radio and stage. His latest book is O Comércio da Literatura

[The Commerce of Literature] (2003), a study of representations of the

literary marketplace in eighteenth-century England. Currently he works

as an Assistant Professor at the University of Coimbra, Portugal. His

latest research is concerned with textual forms in digital media.

Citation reference for this Leonardo Electronic Almanac Essay

MLA Style

Portela, Manuel. " Concrete and Digital Poetics" "New Media Poetry and

Poetics" Special Issue, Leonardo Electronic Almanac Vol 14, No. 5 - 6

(2006). 25 Sep. 2006

<http://leoalmanac.org/journal/vol_14/lea_v14_n05-06/mengberg.asp>.

APA Style

Portela, M. (Sep. 2006) "Concrete and Digital Poetics," "New Media

Poetry and Poetics" Special Issue, Leonardo Electronic Almanac Vol 14,

No. 5 - 6 (2006). Retrieved 25 Sep. 2006 from

<http://leoalmanac.org/journal/vol_14/lea_v14_n05-06/mengberg.asp>

|